| Rural students find college out of reach |

|

(2011/09/13 SCMP) |

|

|

| From a rural boy born and bred in an impoverished town in Chongqing to a postgraduate medical student at the prestigious Peking University, Luo Dasheng best exemplifies how lives can be transformed through hard work at school.

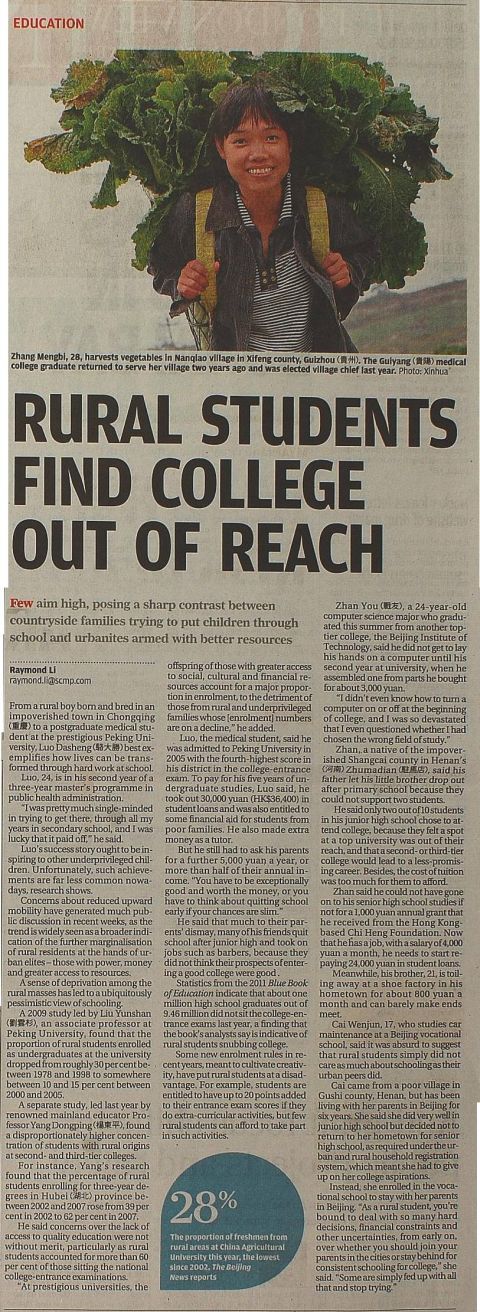

Luo, 24, is in his second year of a three-year master’s programme in public health administration. I was pretty much single-minded in trying to get there, through all my years in secondary school, and I was lucky that it paid off, he said. Luo’s success story ought to be inspiring to other underprivileged children. Unfortunately, such achievements are far less common nowadays, research shows. A sense of deprivation among the rural masses has led to a ubiquitously pessimistic view of schooling. A 2009 study led by Liu Yunshan , an associate professor at Peking University, found that the proportion of rural students enrolled as undergraduates at the university dropped from roughly 30 per cent between 1978 and 1998 to somewhere between 10 and 15 per cent between 2000 and 2005. A separate study, led last year by renowned mainland educator Professor Yang Dongping , found a disproportionately higher concentration of students with rural origins at second- and third-tier colleges. For instance, Yang’s research found that the percentage of rural students enrolling for three-year degrees in Hubei province between 2002 and 2007 rose from 39 per cent in 2002 to 62 per cent in 2007. He said concerns over the lack of access to quality education were not without merit, particularly as rural students accounted for more than 60 per cent of those sitting the national college-entrance examinations. At prestigious universities, the offspring of those with greater access to social, cultural and financial resources account for a major proportion in enrolment, to the detriment of those from rural and underprivileged families whose [enrolment] numbers are on a decline, he added. But he still had to ask his parents for a further 5,000 yuan a year, or more than half of their annual income. You have to be exceptionally good and worth the money, or you have to think about quitting school early if your chances are slim. He said that much to their parents’ dismay, many of his friends quit school after junior high and took on jobs such as barbers, because they did not think their prospects of entering a good college were good . Statistics from the 2011 Blue Book of Education indicate that about one million high school graduates out of 9.46 million did not sit the college-entrance exams last year, a finding that the book’s analysts say is indicative of rural students snubbing college. Some new enrolment rules in recent years, meant to cultivate creativity, have put rural students at a disadvantage. For example, students are entitled to have up to 20 points added to their entrance exam scores if they do extra-curricular activities, but few rural students can afford to take part in such activities. Zhan You , a 24-year-old computer science major who graduated this summer from another top-tier college, the Beijing Institute of Technology, said he did not get to lay his hands on a computer until his second year at university, when he assembled one from parts he bought for about 3,000 yuan. I didn’t even know how to turn a computer on or off at the beginning of college, and I was so devastated that I even questioned whether I had chosen the wrong field of study. Zhan, a native of the impoverished Shangcai county in Henan’s Zhumadian , said his father let his little brother drop out after primary school because they could not support two students. He said only two out of 10 students in his junior high school chose to attend college, because they felt a spot at a top university was out of their reach, and that a second- or third-tier college would lead to a less-promising career. Besides, the cost of tuition was too much for them to afford. Zhan said he could not have gone on to his senior high school studies if not for a 1,000 yuan annual grant that he received from the Hong Kong-based Chi Heng Foundation. Now that he has a job, with a salary of 4,000 yuan a month, he needs to start repaying 24,000 yuan in student loans. Meanwhile, his brother, 21, is toiling away at a shoe factory in his hometown for about 800 yuan a month and can barely make ends meet. Cai Wenjun, 17, who studies car maintenance at a Beijing vocational school, said it was absurd to suggest that rural students simply did not care as much about schooling as their urban peers did. Cai came from a poor village in Gushi county, Henan, but has been living with her parents in Beijing for six years. She said she did very well in junior high school but decided not to return to her hometown for senior high school, as required under the urban and rural household registration system, which meant she had to give up on her college aspirations. Instead, she enrolled in the vocational school to stay with her parents in Beijing. As a rural student, you’re bound to deal with so many hard decisions, financial constraints and other uncertainties, from early on, over whether you should join your parents in the cities or stay behind for consistent schooling for college, she said. Some are simply fed up with all that and stop trying. [email protected] Copyright (c) 2011. South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved. |

This post is also available in: Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Simplified)